👋 Hi and welcome to a new series of blog posts in which we shall deep-dive into Android Security. This series will primarily focus on the Top 10 Mobile security threats as determined by The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) Foundation, the leading application security community in our field.

Whilst these posts focus on the Android platform, many of the ideas and sentiments behind them are totally platform agnostic, as is the OWASP Top 10 list itself.

These posts are also supplementary to my January 2022 talk ‘Don’t get stung by OWASP — An intro into writing code for greater Android Security’ in which I discuss the Top 5 issues in more detail. Please do check my talks page for more details and relevant links. A companion app that demonstrates the issues outlined in the talk is also freely available for download.

Please note that this series is for educational purposes only. Remember to only test on apps where you have permission to do so and most of all, don’t be evil.

Finally, if you enjoy this series or have any feedback, please drop me a message. Thanks!

Introduction

In this first part of my series on Android Security, we shall take a look into the #1 threat to Mobile application security as determined by OWASP, which they outline as being Improper Platform Usage.

On the face of it, Improper Platform Usage seems a somewhat vague statement for something that is supposed to be the burning issue in mobile application security. However, what this title is trying to subtly say is the main threat to the security of our mobile apps is actually us. To put it bluntly, we are the problem! ¹

What do I mean by that hyperbolic statement? Well, it’s usually a developer’s unintentional misuse, negligence or a simple misunderstanding of the Android platform that leads to our most serious security issues.

Nobody can be expected to know the entire platform inside out, nor are developers infallible. Mistakes inevitably happen, but it is my hope that by introducing some of the most common security issues we accidentally write into our code, you will think twice before making the same mistake yourself and save yourself from a potential security disaster.

Example #1 — ‘Mis-Intent-ion’

Please excuse the terrible pun, the first common example of misuse of the Android platform comes within the definition of an Intent. For those that are new to Android, the platform uses the Intent class as a way of starting an action of some kind. That action could be in the form of navigating to a new screen within your app, running a background/foreground service or registering a broadcast receiver to get regular updates from some source. The Intent class provides an easy way of parcelling data and passing it to separate app components and is the most common way to achieve this with the framework.

However, the Android framework also allows for other apps to send and receive Intent instances between them, with the intended purpose of facilitating ‘communication’ between applications. Herein lies the first common pitfall.

To allow for communication between applications, the app component(s) that we wish to be able to receive an Intent must be marked as android:exported=true within the AndroidManifest.xml file. Marking a component with this flag allows for an ‘explicit intent’ ² to be sent by any other application (or the system) to perform the specified action that can be handled by the receiving component.

Additionally, components can also define <intent-filter> blocks within the manifest to specify the types of intents that the activity, service, or broadcast receiver can respond to. Through this definition, another app can use an ‘implicit intent’ ³ to ask the system to show your app as being compatible when offering a specific intent. For example, passing the system an implicit intent to show apps that can handle the URL https://spght.dev might offer a list of installed web browsers. However, something that might not be obvious to beginners is by specifying an intent filter, the component is marked to the system as exportable even if android:exported=true is not explicitly defined within the manifest.

In my experience, it is not uncommon to see app components inadvertently marked as ‘exportable’ when, in fact, they should not be. These incorrectly defined app components pose a huge security risk as they become directly accessible and thus can be potentially exploited.

Exploiting Exports

The main reason mismanaged exporting is so dangerous is due to how trivial it is to find these vulnerabilities in an app and target them.

Malicious actors can manually search reverse engineered applications or use command-line tools such as drozer or slicer to scan for vulnerable exported components. Once gathered, it is possible to use adb to either start the component or craft an intent that performs the hacker’s desired action.

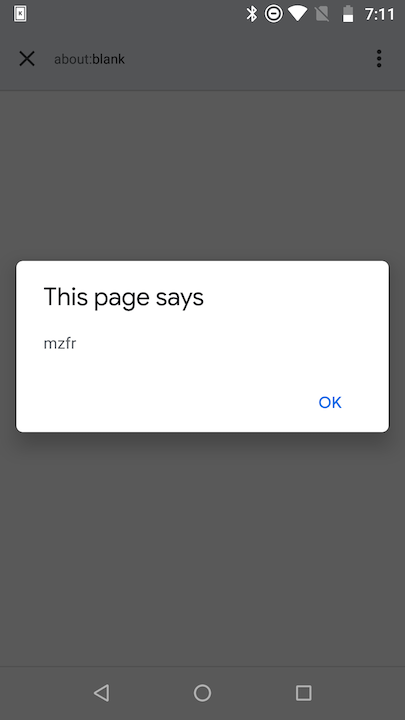

One noticeable real-world example of this was disclosed by the bug bounty hunter, Mehtab Zafar (mzfr), in their November 2020 blog post detailing how a misconfigured ‘deep link activity’ allowed for a cross-site scripting (XSS) exploit to be performed on the official GitHub mobile application. Yikes.

Image credit: https://blog.mzfr.me/posts/2020-11-07-exported-activities

Job Offers

In the companion app written for my talk, this is demonstrated through misconfiguring an activity MainActivity to be exportable despite it normally requiring ‘authentication’ to access it from within the app.

| <activity | |

| android:name=".login.LoginActivity" | |

| android:exported="true"> | |

| <intent-filter> | |

| <action android:name="android.intent.action.MAIN" /> | |

| <category android:name="android.intent.category.LAUNCHER" /> | |

| </intent-filter> | |

| </activity> | |

| <activity | |

| android:name=".home.MainActivity" | |

| android:exported="true" /> |

As MainActivity is exportable, it is possible to simply call adb to have the system open the activity and thus bypass the need for authentication.

| adb shell am start -n dev.spght.owasp/dev.spght.owasp.home.MainActivity |

The Fix

This might all sound somewhat scary, but thankfully stopping this attack vector is as straightforward as ensuring the relevant components within your AndroidManifest.xml file(s) are marked correctly with android:exported.

In fact, as of Android 12 (API 31), it is now a requirement to set the android:exported property on all your Activity, Service, and BroadcastReceiver definitions within your app’s AndroidManifest.xml file(s) when targeting this SDK.

As an extra level of protection, the Android platform also allows for an application to define a ‘custom permission’ through the use of permission elements in the manifest to restrict interactions with its exposed components.

For example, an application can define a ‘signature’ permission that only permits interaction with other applications that share the same permission and are built with the same signing certificate:

| <!-- In the main application --> | |

| <permission android:name="dev.spght.permission.example.MY_PERMISSION" | |

| android:protectionLevel="signature" | |

| android:label="A custom permission" /> | |

| <!-- In the secondary application --> | |

| <uses-permission android:name="dev.spght.permission.example.MY_PERMISSION"/> |

Finally, to avoid GitHub’s fate, it is also a best practice to verify and validate the contents of the Intent you receive when handling data from an <intent-filter>. Do not blindly trust what you receive will be what you expect!

Next up 🚀

In the upcoming posts within this series, we shall explore further instances of ‘Improper Platform Usage’ and more of the OWASP Top 10 for Mobile.

Thanks 🌟

Thanks as always for reading! I hope you found this post interesting, please feel free to tweet me with any feedback at @Sp4ghettiCode and don’t forget to clap, like, tweet, share, star etc

Further Reading

[1] Of course, assuming you are also a mobile developer

[2] An intent that is used to launch a specific app component

[3] An intent that does not name a specific app component, but a general action to be handled