State

State is the pivot in the declarative world. Recomposition happens when there is a modification in the state. There are two methods for altering a state value, which will consequently trigger recomposition:

- Update the inputs of the function.

- Update the state variable, typically done through

mutableStateOf.

Let’s break down how state functions within a composable. Consider the following example:

| @Composable | |

| private fun SimpleTextField() { | |

| var text = "" | |

| TextField(value = text, onValueChange = { | |

| text = it | |

| }) | |

| } |

This composable won’t work because text is just a local variable and its value won’t persist during recomposition.

So, how can we resolve this?

| @Composable | |

| private fun SimpleTextField() { | |

| var text by remember { mutableStateOf("") } | |

| TextField(value = text, onValueChange = { | |

| text = it | |

| }) | |

| } |

In this adjustment, we’ve performed two actions:

- By assigning text with

mutableStateOf(), we declare that the text is now a state, to be precise, a mutable state. - By inserting

remember, we ensure that the value of this text is retained across recompositions.

With these changes, the TextField should now function properly.

Recomposition

Compose starts identifying the scope of changes as soon as there are updates with inputs or states. To illustrate, let’s check this example:

| @Composable | |

| fun Sample() { | |

| var button1 by remember { mutableStateOf("button 1") } | |

| var button2 by remember { mutableStateOf("button 2") } | |

| Column(horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { | |

| // Recomposes when `button1` changes, but not when button2 changes | |

| Button(onClick = { button1 += "1" }) { Text(text = button1) } | |

| Spacer(modifier = Modifier.height(8.dp)) | |

| // Recomposes when `button2` changes, but not when button1 changes | |

| Button(onClick = { button2 += "2" }) { Text(text = button2) } | |

| } | |

| } |

The best way to debug how many times a composable is being recomposed is to use Layout Inspector (Android Studio > Tools > Layout inspector).

In the demonstration, a blue rectangle bordering an element indicates the recomposition scope.

In the demonstration, a blue rectangle bordering an element indicates the recomposition scope.

This behaves as expected, composables recompose independently when reading updated states.

Composition works in the following way:

- Initial State: The entire composable gets composed with the initial values.

- User clicks on

button1: Its state variable updates, triggering a recomposition within the first button’s scope. - User clicks on

button2: Its state variable updates separately frombutton1, leading to recomposition within the second button’s scope.

Understanding Recomposition Scope

Recomposition ensures that the UI is always updated with the latest states. However, repeatedly rendering the entire screen can be costly and impact app performance. To optimize this process, Compose tries to skip redundant renders whenever possible.

Let’s try to understand it by adding another Row to our composable:

| @Composable | |

| fun Sample() { | |

| var button1 by remember { mutableStateOf("button 1") } | |

| var button2 by remember { mutableStateOf("button 2") } | |

| Column(horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { | |

| Button(onClick = { button1 += "1" }) { Text(text = button1) } | |

| Spacer(modifier = Modifier.height(8.dp)) | |

| Button(onClick = { button2 += "2" }) { Text(text = button2) } | |

| // New row added here, expected to recompose when button1 changes. | |

| Row { | |

| Text(text = button1) | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |

Job Offers

Reading state in row trigger recompose to entire composable

The unexpected behavior occurs when reading the state inside the Row scope, causing the entire composable to recompose and this is not desired, we only want recomposition when changes occur in Button1 and the newly added Row.

The reason for this behavior is because of the implementation of Row in Compose. It’s actually an inline function — a very interesting feature of Kotlin. Let’s deep dive into it.

Understanding Inline Functions in Kotlin

Example 1

| fun main() { | |

| print("foo ") | |

| bar() | |

| // prints: foo bar | |

| } | |

| inline fun bar() { | |

| print("bar") | |

| } |

Let’s decompile this into bytecode and see what we’ll get.

| // simplified. | |

| fun main() { | |

| print("foo ") | |

| print("bar"); | |

| // prints: foo bar | |

| } |

(To see the decompiled code in Android Studio, open Tools > Kotlin > Show Kotlin Bytecode > Decompile)

So calling function bar() will always create the copied code to the call site of themain() function.

Example 2

Kotlin supports creating higher-order functions that take functions as parameters. Let’s create a function and pass lambda types () -> Unit to it:

| fun main() { | |

| print("foo ") | |

| bar { | |

| print("bar"); | |

| } | |

| // prints: foo bar | |

| } | |

| inline fun bar(invoke: () -> Unit) { | |

| invoke() | |

| } |

which ends up resulting same bytecode as the previous example.

| fun main() { | |

| print("foo ") | |

| print("bar"); | |

| // prints: foo bar | |

| } |

When calling an inline function, Kotlin does not create any instance of Function behind the scene. Instead, it directly passes the function’s code into the call site where it is invoked. By doing this, Kotlin can reduce the number of redundant objects/memory allocations.

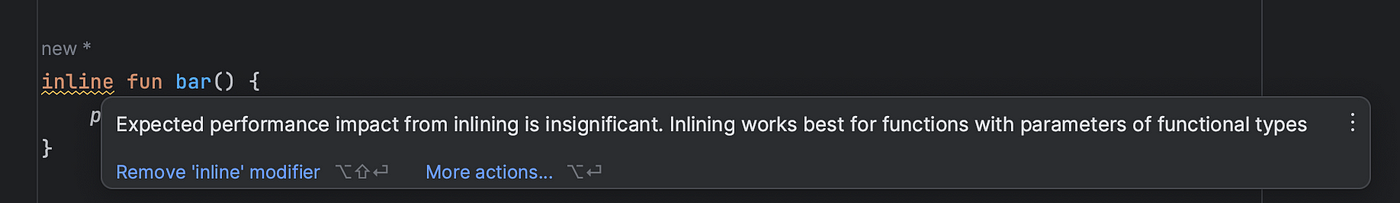

Using inline without lambda is not recommended

In fact, Kotlin recommends not to use inline functions without a lambda type because it may not provide any benefits compared to regular functions. In contrast, by passing lambda types as parameters, we can leverage their nature to treat them as functions without introducing additional scopes.

Using Lambda Types in Compose

Returning to our previous discussion, the unexpected behavior occurs when we add a new element and read the state hence triggering a recomposition to the nearest scope.

This behavior is due to the implementation of functions like Row, Column, Box, and Layout in Compose. These functions are marked as inline, which means they don’t create separate scopes but pass their call block directly to the call site.

| @Composable | |

| inline fun Row( | |

| modifier: Modifier = Modifier, | |

| horizontalArrangement: Arrangement.Horizontal = Arrangement.Start, | |

| verticalAlignment: Alignment.Vertical = Alignment.Top, | |

| content: @Composable RowScope.() -> Unit | |

| ) { | |

| // implementation details | |

| } |

To address this issue and ensure that the sample composable recomposes only for the intended views, we can create a new function with a lambda type and call it as follows:

| @Composable | |

| fun MyRow(content: @Composable () -> Unit) { | |

| content() | |

| } | |

| @Composable | |

| fun Sample() { | |

| var button1 by remember { mutableStateOf("button 1") } | |

| Column(horizontalAlignment = Alignment.CenterHorizontally) { | |

| // other composables | |

| MyRow { | |

| Text(text = button1) | |

| } | |

| } | |

| } |

By introducing the non-inline function MyRow with a lambda parameter, we can control the recomposition scope. The content passed to MyRow will be treated as one level below the call site, preventing unnecessary recompositions in the outer scope.

Here is our final result ❤️

Conclusion

We often don’t need to worry too much about handling recomposition and redundant renders in Compose. It will try to skip as much as possible. However, taking advances in lambda types will help us a lot in improving performance or ensuring every portion of our UI is always validated with the committed states.

One noteworthy example is when dealing with resource-intensive operations, such as loading large bitmaps or animating views during scroll states. Performing such operations directly at the composition level can be expensive and may lead to UI glitches or janky animations.

To address this, we can perform these resource-intensive operations in the background, outside the composition. By using a lambda type, such as providers: () -> Unit, we can pass the result of these operations to the UI at specific times or intervals.

Further Reading:

I highly encourage you to explore the articles mentioned above to gain a deeper understanding of how recomposition works in Compose:

Hello there 👋

My name is Phat, I work as Mobile Lead Engineer at Lazada, Alibaba. I write about Mobile and Software Engineering in general. Feel free to drop me a message or leave a comment if you spot something interesting in my post. You can always find me on TwitterandGithub.

Happy reading and remember to give it a clap if you have liked the post so far.

This article was previously published on proandrdoiddev.com

Photo by

Photo by